The book is called "Design for the Real World" by Victor Papanek.

It's super old. Written in 1971 I believe. But like any designer will tell you, the principles of design remain the same throughout time.

My assignment was to read the first chapter, titled "What is Design?"

Victor begins his book by clearly drawing the line between what is and what is NOT design.

"Design is the conscious effort to impose meaningful order".

Everyone is a designer. Whether it be organizing your home in a certain way, preparing your clothes for the week, or making coffee, you are a designer.

Patterns in nature however are not design. The way that petals grow and assemble in a Fibonacci sequence is beautiful, however it is not design. The flower is only concerned about exposing maximum surface area for photosynthesis.

We love to organize things in a way that's especially easy to understand. When coins are organized in according to size and shape, they are pleasing to the eye because it's easy to understand.

When a problem is presented, design can never have one true answer like Mathematics. There are an infinite number of possible answers on a continuum.

"Design must be meaningful"

The word meaningful replaces all the other meaningless words like "beautiful", "ugly", "abstract", etc. We as humans respond to that which is meaningful.

"The mode of action by which a design fulfills its purpose is the function."

The author often would be asked by students, "Should a design be functional or be aesthetically pleasing?"

The problem with that statement is that the two are not mutually exclusive. In fact, aesthetics is what even contributes to the functionality of a product.

If a dining table is nice and sturdy, however it looks something you would lie on to get surgery on, it does not serve its purpose.

Aesthics and use are just 2 of the 6 parts of...

THE FUNCTION COMPLEX

Papatek guides us through each of the 6 parts of the Function Complex.

1. Method

The interaction of tools, processes, and materials

Papanek goes on to provide examples of some ways tools, processes, and materials were combined to produce an "awesome" (read: not that awesome) product.

So apparently this horse is supposed to be amazing because Alexander Calder needed to use boxwood because it gave him the specific color and texture he needed. But boxwood only came in small sizes so he has to connect them. Then to top it off, he added walnut on the top to finish it off.

I honestly don't get why that's such a big deal...

Then Papanek goes on to explain how the Swedish settlers in Delaware used resources around them to make log cabins and then described how this one machine makes styrofoam buildings in a really efficient way.

I guess these things were considered impressive in 1971.

2. Use

Does it work?

The primary example Papatek uses to explain "use" is the automobile.

I did learn something really peculiar is that one of the first criticisms of the car is that it didn't know how to make its way home on it's own unlike a horse. Back in the day when fellas would get drunk they would just hop on their horse and it would take them home. That sounds pretty sweet!

However Papatek points out that there became many unintended effects of the automobile. It became a place to sleep on the go and even a place for young people to copulate out of sight of their parents.

The car also had the unintended consequence of becoming a symbol of status. However when people began to fly more and had to rent cars, the "status" importance of cars went down again.

The main idea of this section is that the side effects of cars has come and gone, however the primary purpose of the car which is to get you from point A to point B efficiently has always been there and thus is still a part of our every day lives.

He does conclude this section with the notion that electric cars may make a comeback... back in 1971 haha.

Let's see how well the Tesla Model 3 sells.

3. Need

The economic, psychological, spiritual, technological, and intellectual needs of a human being are usually more difficult and less profitable to satisfy than the carefully engineered and manipulated 'wants' inculcated by fad and fashion.

Paptek begins to get very psychological and philosophical in this section.

He begins to talk about the need for "security through identity". People feel a sense of security to walk on beaten paths and find security within crowds. They wear pseudo-military uniforms to act out a role of one that has lived a strenuous life.

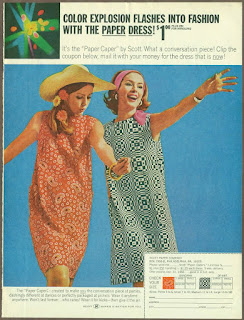

He then talks about the Scott Paper Company and paper dresses.

Disposable paper dresses were sold for really cheap and even as low as 99 cents. However the prices could've even dropped to 40 cents. The dresses could've even gone for $20 to $150. That's crazy for the 70s. However industry and its greed chose to ignore the important need-fulfilling function of the design. The design was means to mean disposability was economically feasible for the consumer.

He claims that in our society we have become over specialized. And that we are encouraged to become an "expert" on whatever we become. However if the "expert" of something does not have the right morals, it doesn't matter.

4. Telesis

The deliberate, purposeful utilization of the processes of nature and society to obtain particular goals

Under the rule of Tokugawa Shogunate, Japan was cut off from the Western rule for over 200 years and grew in a "pure" form.

This grew a lot of intrigue from the Western World and many sought for adopt things of the culture.

The things found in a Japanese household work in harmony, it is a great example of telesis.

The floors of a traditional Japanese home are covered by floor mats made out of rice straw. They are meant to reduce noise as well as collect dirt between its cracks. Periodically these mats would be replaced.

Western shoes like leather-soles shoes or spiked heels would destroy the surface of these mats, rendering them useless.

The Japanese home is a system. The sliding doors give acoustic properties influencing the design and development of musical instruments and structure of Japanese speech, poetry, and drama.

As a Westerner, you cannot take things from Japanese culture and just put them ad hoc. They don't work as they are intended to be and can even prove to be harmful to the system.

"Element cannot be ripped out of their telesic context without impunity"

5. Association

Our psychological conditioning, often going back to earliest childhood memories, comes into play and predisposes us, or provides us with antipathy against a given value.

Time after time designs have been generated more by inspired guesswork and charts than the genuine wants of the consumer.

From our earliest time we have been conditioned by our surroundings.

But before you continue, YES YOU, take a look at these two drawings and tell me.

Which one of these would you name "Tekete" and which would you name "Maluma"???

If you are like everyone else in the world, you would say the one of the left is "maluma" and the one on the right is "takete".

Even totally meaningless sounds and shapes can mean the same thing to all of us.

As a designer is it important to be mindful of these associations and serve the wants of the consumer.

6. Aesthetics

A theory of the beautiful, in taste and art.

Papatek immediately states that the dictionary definition listed above does not help at all in figureing out what aesthetics is.

However we do know that aesthetics is important as a tool in exciting us and filling us with delight.

Papatek uses the Last Supper by Leonardo Davinci to explain his last point.

Davinci not only had to make this aesthetically beautiful, he also had to:

Use the right type of method to find the correct combination of paints and brushes.

Serve a spiritual need for the people.

Provide reference points from the Bible by working on the associational and telesic plane.

And its use is to cover up a wall. hahahaha.

As closing points. Next time you see something that beautiful, in order to get more of a designer's eye, look for the other aspects of the Function Complex.

Beyond the primary 6 functional requirements, designers strive for: precision and simplicity.

The example he gives is the Mathematician Euclid's Proof that the number of primes is infinite.

His proof is that 1 x 2 x 3 x 4 ... x P + 1 is always going to be prime. Therefore as long as there are an infinite amount of numbers, there will be an infinite number of prime numbers (Sorry if this doesn't make sense. It's honestly not that important to drive home the point).

In conclusion this seems like one of those articles that every designer has read for their studies to become a designer.

I'm glad I read it but I don't think I'll ever read it again haha.

No comments:

Post a Comment